The Boys & Girls Clubs of America Started Here

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of Connecticut Explored, a magazine published by a consortium of organizations that represent the best heritage, educational, and arts organizations in the state. It's also a nonprofit. Please subscribe.

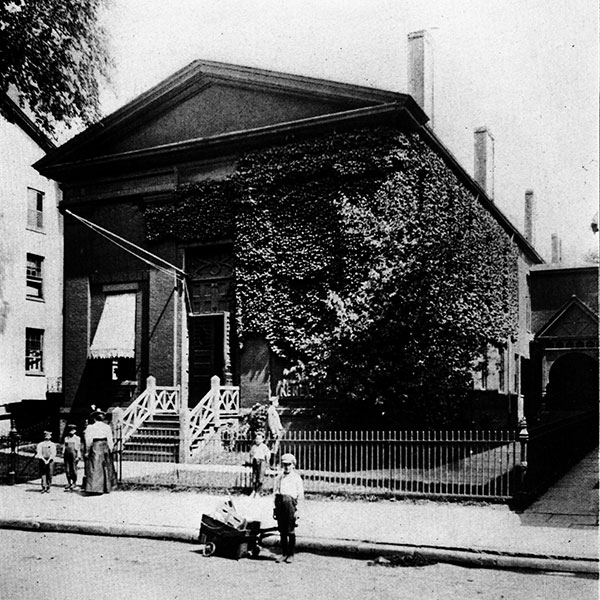

The Good Will Club, an early form of the Boys & Girls Clubs, operated in this building at 96-100 Pratt Street in Hartford from 1889 to 1910. A contemporary Hartford Courant article identifies the woman in the photograph, taken in 1908, as Superintendent Mary Hall. From “Good Will Club Thirteenth Annual Report, 1910,” courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

By KEVIN FLOOD

The Boys & Girls Clubs of America is the largest youth organization in the United States, serving more than 4.2 million young people in more than 4,000 clubs around the world.

And it all began in Hartford, Connecticut.

The youth-club movement started here in part because of European immigration and in part because of Hartford’s place in the forefront of 19th-century industrialization. Burgeoning factories fueled a doubling of the city’s population in the 1850s, from 13,500 to more than 29,000. This was a time before public parks were common, and while the adults went to work, children of factory workers often played in the streets. As Peter C. Baldwin describes it in "Domesticating the Street: The Reform of Public Space in Hartford, 1850-1930" (Ohio State University Press, 1999):

… play could easily stray into violence, vandalism, or petty thievery. Boys enjoyed throwing snowballs at peddlers and pedestrians … Some would show bravery by stoning children of other ethnic groups, starting brawls, swiping food from sidewalk displays, and setting fires.

Some middle-class Protestants feared being overwhelmed by waves of unruly immigrants. Others began to see it as their religious and social duty to save children from the streets and give them the skills to live productive, orderly lives. Among these were four women: Mary Goodwin, her sister Alice H. Goodwin, Alice’s neighbor Elizabeth Hamersley, and Louisa Bushnell.

In 1860 the Goodwin sisters, Hamersley, and Bushnell got permission to use a room at the Morgan Street Mission School as a place for boys to temporarily get away from the streets and, it was hoped, improve their appearance, manners, and morals, according to club records summarized in a 2010 booklet written by Sandra Bender Fromson for the club’s 150th anniversary. They called their organization the Dashaway Club. But the next year the Civil War broke out, and attendance fell as boys joined the military or went to work in factories. Soon, the club closed

Attempts to revive it were made over the next two decades. In 1867 the Sixth Ward Temperance Society—sometimes called the Temperance Dashaway Society—began meeting in a local home and eventually in a back room of the mission. As the name implied, participating boys had to take a pledge to abstain from alcohol. The organizers, Fanny Morris Smith and Jennie Owen, borrowed furniture, pictures, and books to make the room feel like a middle-class home. The boys read aloud, played games, wrote and performed plays, and sang—even reviving "The Dashaway Song," which Hamersley had written for the original club. Again, however, membership dwindled over time until the organization was forced to disband.

But then came Mary Hall. The daughter of a prosperous miller in Marlborough, Hall became Connecticut’s first female lawyer in 1882 and emerged as a leader of social reform on several fronts in Hartford, including women’s suffrage. Her biggest impact, however, came in founding the Good Will Club. Hall had volunteered three nights a week for a year at an evening school for boys, giving lessons on various subjects and reading aloud Horatio Alger stories, according to Baldwin. As her popularity spread, she began holding the lessons in the building that housed her law office. Hall and her supporters saw the need for a new organization, and on April 2, 1880 the Good Will Club was formally launched. The boys paid dues of 10 cents a month, and help in raising more funds came from prominent citizens such as Hartford Times publisher Alfred E. Burr.

The Goodwill Club diverged from the earlier clubs by operating as a secular organization. Hall insisted that any of the rapidly growing number of Catholic and Jewish children in the city be allowed to join without fear of being pressured to change their religious beliefs. She put this notion to the test early on, when some Catholic parents began pulling their children from the club because of its new affiliation with the Young Men’s Christian Association. As one of the "historical sketches" prepared by the club later described it, she simply cut ties with the YMCA.

The club’s membership grew rapidly in the 1880s, and similar clubs began springing up in other eastern cities like Providence (1868), New York (1876), and Boston (1893). In Connecticut, New Haven’s club was founded in 1871, Bridgeport’s in 1887, Waterbury’s in 1888, and New Britain’s in 1891.

The growth of Hartford’s club required it to move from one temporary facility to the next. Burr and his colleague at the rival Hartford Courant, editor David Clark, led a campaign to raise money for a permanent headquarters. With the help of many small donations and a particularly big one ($17,000) from wholesale grocer Henry Keney, they raised $25,000—enough to buy a former women’s seminary on Pratt Street in 1889. The 30,000-square-foot facility allowed the club to dramatically expand its offerings. In addition to the usual indoor recreation and classes, boys could now learn plumbing, carpentry, knitting, cooking, military drilling—and knitting. The club also launched its own newspaper, the Good Will Star, with the boys using a donated press to print it. Many businesses, in fact, donated tools and equipment for industrial-arts classes. There were other in-kind donations, too. By 1905 the club library had 2,000 volumes. Boys consumed the books so voraciously that by 1910 there were complaints that all that reading interfered with their schoolwork. A one-book-per-week limit was imposed.

Meanwhile, with clubs spreading as far south as Nashville and as far west as San Francisco, an affiliation movement began. Leaders of 53 clubs—with Mary Hall representing Hartford’s—met in Boston in 1906 and formed the Federated Boys Clubs. In 1931 the organization became the Boys Clubs of America.

Meanwhile, back in Hartford, the Pratt Street clubhouse had become cramped by 1910. Another fundraising campaign and the donation of land by the Keney family led to the construction of a bigger clubhouse on Ely Street, near the Keney Clock Tower. This served as the club’s home until the late 1950s, when city plans to redevelop the neighborhood forced another relocation. The club had by this time opened at branch in the southwest section of the city, and so the new headquarters was built on the corner of Granby and Nahum streets, and called the Northwest Club. More branches followed in the 1960s, based on demand in the city’s public housing projects.

Amid the physical changes came name changes. In 1943 the club changed its name to the Good Will Boys Club. In 1957 it became the Boys Club of Greater Hartford. In 1992, reflecting a long-awaited change in the club’s membership, it became the Boys & Girls Clubs of Hartford.

Today the organization has three freestanding facilities: the Asylum Hill Boys & Girls Club on Sigourney Street, which also houses the Hartford headquarters; the Southwest Boys & Girls Club on Chandler Street; and the Trinity College Boys & Girls Club, which represents the first partnership in the nation between a Boys & Girls Club and a college. The club also operates in several Hartford and Bloomfield public schools.

Samuel S. Gray Jr., president and chief executive officer since 2007, points to the early club’s instruction in trades, calling it well ahead of its time. “People talk about workforce-development initiatives now, but that’s what we did back then,” he says. "We gave technical and trades opportunities to our young people. We were very much an industrial-arts organization."

Still, Gray thinks Mary Goodwin, Alice H. Goodwin, Elizabeth Hamersley, and Louisa Bushnell would recognize the club today. "If you look at our core principles, they’re very much the same." Chief among them, he says, is "keeping those fees affordable, so that any child can join."

"Today," he notes, "for a kid to attend our after-school program with homework help, robotics, sports leagues, and so forth, it’s $10" annually. In a time when day-care programs are expensive—if they can be found at all—that makes a difference in more ways than one, Gray says. Upwards of 70 percent of club kids come from single-parent homes, he explains, and in those homes, 87 percent of the parents say the club allows them to have full-time jobs. "That’s impact, right there."

The impact is set to extend next to Hartford’s South End, the one section of the city not served by the club. A $20 million clubhouse—complete with a gym, classrooms, and a computer lab—is planned for construction on three city-0wned acres behind the Alfred E. Burr Elementary School. "We want to be where the kids need us," Gray says.