Trivia Questions

Dedicated to the memory of Patricia Reardon Monahan (1950-2000.)

To get new trivia questions, sign up for the free weekly newsletter.

September 21, 2020

Q: Who was known as the "Sweet Singer of Hartford"?

The poet Lydia Sigourney. As journalist Norma Buchanan described her in a 2019 article for the Hartford Courant:

"Sigourney (1791-1865) was the most celebrated Hartfordite of her day and the best-known female poet in America, with avid readers in every corner of the country and a reputation that reached to the drawing rooms of Europe. Periodicals competed for the right to publish her poetry. At the height of her fame, in the late 1840s, she was as popular as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow."

But thanks to her grandiose style and superficiality, her popularity didn't extend much past her own demise in 1865. Nevertheless, the Hartford places named after her include Sigourney Street and Sigourney Square Park. She is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery

April 1, 2020

Q: From 1948 to 1962, the CBS radio network presented a serial drama about a Hartford-based insurance investigator who traveled the country to get to the bottom of suspicious claims, which almost always turned out to center on murder or some other crime. The investigator/title character narrated cases by reading from the expense reports he sent back to Hartford. Thus, at the beginning of each episode, an announcer introduced “the transcribed adventures of the man with the action-packed expense account, America's fabulous freelance insurance investigator …”

What was the name of this show?

“Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar.” The show originally ran from 1948 to 1954, with weekly episodes and several actors playing Johnny. The next year, CBS revived it as a 15-minute, five-nights-a-week show, with Bob Bailey playing Johnny. This version, the best-known one, ran for 13 months. “Johnny Dollar” then reverted to a weekly program and went off the air for good in 1962.

Sources:

The Thrilling Detective Website;

The Old-Time Radio Researchers Network, via Archive.org;

“On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio,” via Google Books”. See pages 742-743;

www.yourstrulyjohnnydollar.com, which sells episodes in CD or MP3 format.

Some episodes can be found on YouTube.

February 16, 2020

Q: What was the 91 Club?

When the roof of the Hartford Civic Center collapsed in the early hours of January 18, 1978, it left the New England Whalers—then of the upstart World Hockey Association—without a home. But the team’s management quickly lined up the Springfield (Mass.) Civic Center as a temporary home, and loyal Hartford-area fans began trudging up Interstate 91 to see their team. They became known as the 91 Club. By the time a rebuilt Hartford Civic Center opened a little more than two years later, the club had 4,200 members. It was a new day in more ways than one: During their Springfield sojourn, the Whalers had changed their name to the Hartford Whalers and joined the National Hockey League.

Sources: “Hartford: An Illustrated History of Connecticut’s Capital,” by Glenn Weaver and Michael Swift, published in 2003 by the American Historical Press, and the July 29, 2010 Hartford Courant (“The Hartford Whalers Historical Timeline.”)

January 26, 2020

Q: How did the Frog Hollow neighborhood get its name?

“A marsh gives the neighborhood its name,” journalist and author Susan Campbell wrote in her 2019 book, “Frog Hollow: Stories from an American Neighborhood.” In colonial times, the neighborhood was largely farmland. When a well was dug on the Babcock farm, near what is now the corner of Park and Washington streets, the water gushed with such force that “the men digging the well had to scramble to avoid drowning.” Campbell also noted that some have “claimed that the ‘frog’ came from the influx of French Canadians who began moving to the hollow in the 1850s to work in the factories.”

January 10, 2020

Q: Of course, Hartford Public High School once stood atop Asylum Hill, at the corner of Asylum and Hopkins streets—until it was obliterated in the 1960s to make way for Interstate 84. But where was the school located before moving to Hopkins Street?

In a wood-frame building at the corner of Asylum and Ann Uccello streets, starting in 1847. The school outgrew these quarters and moved into a new brick building on Asylum Hill in 1869. Fire destroyed that building in 1882. But by 1884, students occupied a rebuilt school designed by architect George Keller. This is the spectacular building you may know from photos and postcards.

For more on the Hartford Public’s history, visit its website.

December 9, 2019

Q: In 1948, the city named the Windsor Street underpass after Rocco D. Pallotti. Which of these was he?

A) a hero of World War II;

B) a politician; or

C) a police officer.

The answer is B. As an alderman, Pallotti had pushed hard for construction of the underpass, which eliminated a dangerous street-level railroad crossing. He was a state senator when the city’s Common Council voted on January 2, 1948 to put his name on both the underpass and another of his projects, the Riverside Park swimming pool. Later, he would serve as deputy commissioner of the state Department Motor Vehicles. For more on his colorful and often controversial career, read this obituary from the December 26, 1985 Hartford Courant.

November 16, 2019

Q: The first Hispanic woman to serve in the Connecticut General Assembly was elected by Hartford voters in 1988. Who was she?

A: Maria C. Sanchez. You can read about her extraordinary life of service here, at the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame site.

October 30, 2019

Q: By tirelessly championing modern art, Wadsworth Atheneum Director A. Everett "Chick" Austin put Hartford on the art world map from the late 1920s through the early 1940s. In December 1934, he lured a young artist who was then little-known in the U.S. to give a lecture at the Atheneum. That artist would become one of the most famous of the 20th Century. Who was it?

A: Salvador Dalí. In his 2000 biography of Austin, "The Magician of the Modern," Eugene R. Gaddis described the surrealist’s appearance in the Atheneum’s Avery Theater that night:

"There were rumors that [Dalí] would appear with a loaf of bread on his head, but instead the audience saw a slim young man in a suit with sleek black hair and a thin moustache—in those days barely beginning to curl up at the ends. In introducing the program, Chick seemed, according to New York Tribune columnist Joseph W. Alsop Jr., ‘more apprehensive than at any of his previous efforts to make Hartford the new American Athens.’"

The talk, which Dalí gave in French, was preceded by a screening of a surrealist movie he had made with Luis Buñuel in 1928. Afterward, according to Gaddis, Dalí uttered his most famous dictum—"The difference between me and a madman is that I am not a madman!"—for what may have been the first time. Sadly, there weren’t many witnesses. The Avery was two-thirds empty.

October 18, 2019

Q: Saturday, July 26, 1941, marked the end of an era that had lasted more than 50 years in Hartford. What happened?

A: The last of the city’s trolleys were retired in favor of buses. The Connecticut Company, which operated the trolley line, began mixing buses into its service in 1925. By early 1941, the company was petitioning state utility officials for permission to finish the transition.

In an editorial supporting the move, the Hartford Courant observed that with the advent of the automobile, “the trolley business began to lag. As these vehicles multiplied, the street railways found it increasingly difficult to make both ends meet. To find the point where higher fares would produce the needed revenue without a disastrous falling off in traffic presented a nice problem.” Though it hadn’t solved that problem yet, the bus was “generally welcomed by the public because of its quietness and flexibility,” the editorial said, adding that “the public certainly cannot do without the service it provides."

The editorial went on to predict that the Connecticut Company’s petition wouldn’t meet much opposition. That proved to be true; in fact, the Courant reported after a public hearing that no one spoke in opposition. Still, feelings apparently ran high on the trolleys’ last day of service, with the Courant reporting they were accompanied by hordes of honking cars and even obstructed temporarily by a flaming trash pile at Barbour and Judson streets.

For more on the demise of the streetcar across the U.S. (including the oft-made charge that General Motors engineered it), see this 2015 Vox article.

Sources: Hartford Courant, January 16; January 28, and July 28, 1941.

October 11, 2019

Q: What does the “TIC” in WTIC stand for?

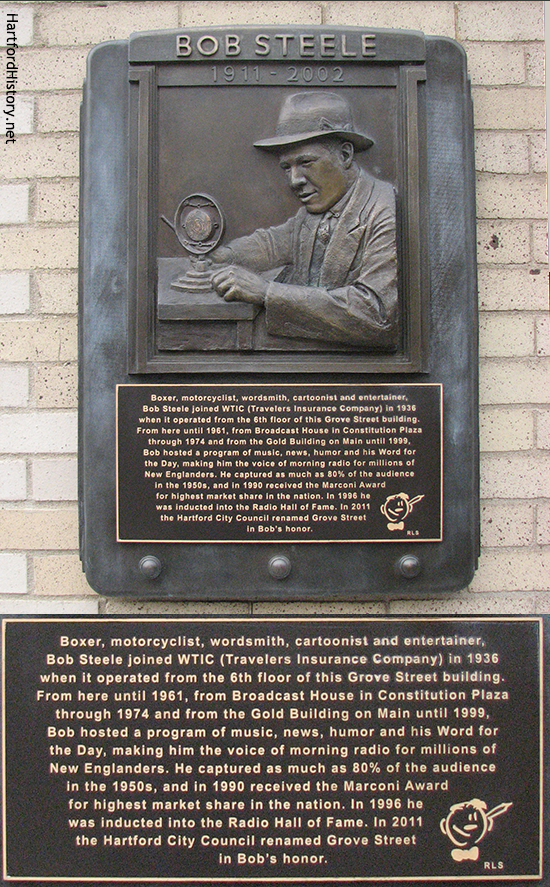

A: Travelers Insurance Co., the first owner of the AM radio station. The U.S. Department of Commerce awarded Travelers a broadcast license on January 25, 1925, with broadcasting beginning on February 10 from the sixth floor of 26 Grove Street, an office building adjacent to the Travelers tower. (Interestingly, WTIC originally occupied 860 on the dial, not moving to its current spot at 1080 until 1941.) Travelers sold the station to the Chase family in 1974.

Today, a plaque affixed to a corner of WTIC’s original home memorializes the broadcaster who for decades dominated morning radio in the Hartford region, Bob Steele. The section of Grove Street between Prospect Street and Columbus Boulevard was renamed in his honor in 2013.

For more on WTIC’s history, including some wonderful photos, visit HartfordRadioHistory.com. For more on Bob Steele, check out the new biography by Paul Hensler, "Bob Steele on the Radio: The Life of Connecticut’s Beloved Broadcaster." It’s available at McFarlandBooks.com.

September 27, 2019

Q: One of Hartford’s most-traveled streets was known as Hubbard Street until 1873, when it received its current name. What is that street?

A: Sisson Avenue. It’s named for Albert Sisson, a wholesale grocer who built a 14-room mansion on the street in the mid-1860s. He also served on the city’s board of selectmen and helped found the Asylum Avenue Baptist Church. The street was renamed in his honor by 1873; he died in 1886. Following the death of his wife in 1898, the mansion briefly served as a hospital for scarlet fever patients, then became a home for wayward girls operated by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. The Sisters added five more buildings to the property before selling it in 1979. Today, the complex is operated as the Shepherd Park Apartments for the elderly.

(Sources: “How Hubbard Street Turned into Sisson Avenue,” Hartford Courant, March 7, 2007, and “Structures and Styles: Guided Tours of Hartford Architecture,” by Gregory E. Andrews and David F. Ransom, published in 1988 by the Connecticut Historical Society and the Connecticut Architecture Foundation.)

September 19, 2019

Q: The $133 million renovation of Weaver High School has been drawing rave reviews. It’s named after Thomas Snell Weaver. Who was he?

A: Weaver was superintendent of Hartford schools from 1901 until his death at age 77 in 1922. Prior to becoming superintendent, the Willimantic native had a long career in New England newspapers, culminating in becoming a political reporter for the Hartford Courant in 1893. The original Weaver High—now the Martin Luther King School on Ridgefield Street—was named for Weaver when it opened in 1923. That school is undergoing its own renovation, with re-opening set for Fall 2020. (Source: “The Names of Hartford’s Public Schools and Other Historical Notes,” compiled by Wilson H. Faude for the Hartford Public Schools and Hartford Public Library in 2011.)

September 6, 2019

Q: A famous Hartford restaurant opened in the basement of the United States Hotel on State Street in 1845. Name it.

A: The Honiss Oyster House, the oldest restaurant in the city when it finally closed its doors in 1982. Its renowned oysters attracted such celebrities as Mark Twain and Buffalo Bill Cody. (Sources: “Yesterday’s Connecticut,” by Malcolm L. Johnson, and “Any Month with an ‘R’ in It: Eating Oysters in Connecticut,” an article on ConnecticutHistory.org.)

August 28, 2019

Q: Multiple-choice trivia question! Campfield Avenue is named after a military encampment created during which of these wars: a) King Philip's War; b) the Revolutionary War; or c) the Civil War.

A: The Civil War. The encampment, located just off what is now Barry Square, served as a mustering-in spot for many Connecticut regiments. The city accepted Campfield Avenue in 1898, as the South End underwent a development boom that lasted well into the 1920s. The encampment site, bounded by Campfield Avenue and Bond Street, was donated to a volunteer group called the Camp-Field Monument Association, which sought to build a memorial that evoked the spirit of Connecticut volunteers in the war. In 1900, it unveiled a statue of Griffin A. Stedman, a Hartford native who led troops at the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Cold Harbor before dying on August 7, 1864 from wounds he had suffered the day before at the Union siege of Petersburg, Va. He was promoted from colonel to general as he lay dying. He was 26.

Sources: “History of Hartford Streets,” by F. Perry Close, published in 1969 by the Connecticut Historical Society; the Cedar Hill Cemetery Foundation; and Hartford Courant articles dated January 19, 1899 (“Camp-Field Monument. Effort to Raise Funds Meeting with Success,”) October 4, 1911 (“Campfield Park Was Camping Ground,”) and March 9, 1919 (“When the Cannon Balls Were Rolling on the Ground.”)

August 12, 2019

Q: Dillon Stadium, which recently underwent a complete renovation, opened in 1935 as Municipal Stadium but was renamed in 1956 to honor James H. Dillon. Who was he?

A: He was the city’s longtime recreation director. At the time of the honor, Dillon already had spent 35 years on the job. He retired several years later and died in 1963, at age 73. Here is the Hartford Courant’s news obituary, which lists some of his many accomplishments. To get an idea of how the stadium looks now, watch this video from the professional soccer team that now calls it home, the Hartford Athletic.

August 2, 2019

Q: Hermann P. Kopplemann (1880-1957) rose from the immigrant neighborhood of Hartford’s East Side to found H.P. Kopplemann and Co., which eventually became Connecticut’s leading distributor of newspapers and magazines. But it was in the political realm where Kopplemann did his most important work, achieving several “firsts” in the process. What were they?

A: He was the first Jew to serve as president of the City Council, the first Jew elected to the state Senate from Hartford, and the first Jew elected to Congress from Connecticut. Kopplemann’s “genuine affection for poor working men and women”—especially those in his childhood neighborhood—helped earn him the nickname “father of the East Side,” according to David G. Dalin and Jonathan Rosenbaum, in their book, “Making a Life, Building a Community: A History of the Jews of Hartford.” In the legislature, Kopplemann sponsored the Connecticut Widows’ and Dependent Children’s Pension Act of 1920, a forerunner of the national Social Security system. Among the other achievements in which he played instrumental roles: a state pension law for teachers, the state’s first comprehensive workers’ compensation program, and the law prohibiting those under the age of 16 from working in factories.

April 14, 2019

Q: A longtime Hartford business was the setting for one of painter Norman Rockwell’s more famous covers for the Saturday Evening Post, appearing in the May 19, 1956 issue. Name the business.

A: Harvey & Lewis Opticians on Pearl Street. Rockwell went there to get inspiration for his painting “New Glasses,” which you can view here, on the Facebook page of his estate. Read more about Rockwell’s visit on the excellent history page of the Harvey & Lewis website.

January 27, 2019

Q: What Hartford institution disappeared on October 20, 1976?

A: The Hartford Times. Launched in 1817 as the Hartford Weekly Times, the paper evolved into an afternoon daily that competed tooth-and-nail with the Hartford Courant. Editorially, it cast itself as the working person’s newspaper, in contrast to the more conservative and establishment-supporting Courant. By the 1970s, however, its circulation had dropped by half from the previous decade. In his “Images of Hartford, Volume III,” Wilson H. Faude blamed the Times’ closing on “a combination of the rising influence of television, union demands and costs, and the growth of suburban readership.” Frequent turnover in management didn’t help either; the Times’ final owner was the Register Publishing Co. of New Haven.

The Hartford Times Building, which served as the paper’s final home from 1920 onward, now serves as the face of the University of Connecticut’s Hartford campus.

January 13, 2018

Q: For whom is Murphy Road named?

A: Francis S. Murphy, editor and publisher of the Hartford Times. It’s no accident that the road, created in the 1960s, runs parallel to Brainard Field. Murphy was a longtime booster of local aviation and served as chairman of the Connecticut Aeronautics Commission. (The original terminal at Bradley International Airport also carried his name.)

Source: "History of Hartford Streets," by F. Perry Close, published in 1969 by the Connecticut Historical Society.

December 30, 2018

Q: What city institution—still with us—was founded in response to a steam boiler explosion that killed 21 and seriously injured as many as 50 on March 2, 1854, at the Fales and Gray railroad-car factory near Dutch Point?

A: Hartford Hospital. Alarmed at the lack of facilities to care for such a large number of injured people, citizens held a public meeting two months to the day after the explosion and voted to create a public hospital. Until 1892, it provided medical services free of charge.

Sources:

- "Hartford: An Illustrated History of Connecticut's Capital," by Glenn Weaver, published in 1982.

- "Fales & Gray Explosion—Today in History: March 2," on ConnecticutHistory.org.

- "How A Deadly Factory Explosion In 1854 Fueled The Creation Of City's First Hospital," Hartford Courant, September 15, 2014.

- History page of HartfordHospital.org.

December 7, 2018

Q: What key part of Hartford's infrastructure is named after a man who grew up in the city and was killed at the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor?

A: The Conland-Whitehead Highway, which connects traffic between downtown's Pulaski Circle and Interstate 91, is named in part after U.S. Navy Lt. Ulmont I. Whitehead Jr., a 1933 graduate of Bulkeley High School. His remains, along with those of 1,101 other servicemen, are entombed in the sunken USS Arizona.

For more on Whitehead's short but accomplished life, read this 2002 Hartford Courant article.

November 17, 2018

Q: What major artery of Hartford was originally called Talcott Mountain Turnpike?

A: Albany Avenue. It was laid out as Talcott Mountain Turnpike by the Connecticut General Assembly in May 1678 but became known as the stage road to Albany, New York. It was deeded to the city by the Talcott Mountain Turnpike Company in 1854.

Source: "History of Hartford Streets," by F. Perry Close, published in 1969 by the Connecticut Historical Society.

Previous questions

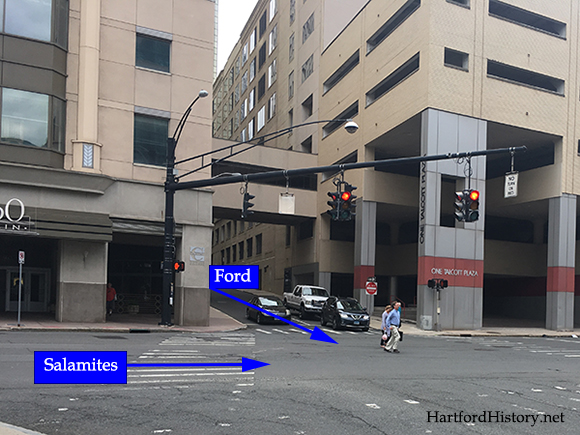

Q: Hartford found itself in the national spotlight on October 14, 1975, when a limousine carrying President Gerald R. Ford collided with a car full of teenagers at a city intersection. Thankfully, no one was seriously hurt. At what intersection did this occur?

A: Talcott and Market streets, downtown. Ford had just spoken at a Republican fund-raising dinner at the newly opened Hartford Civic Center. His motorcade, bound for Bradley International Airport, turned down Talcott Street, toward Interstate 91. On Market Street, 19-year-old James Salamites of Meriden was driving north in his mother’s Buick LeSabre, with five friends as passengers. Hartford police had blocked off other intersections along the route, but not this one. Salamites had the green light; Ford’s driver, assuming Market Street had been blocked off, didn’t stop either. He spotted Salamites and tried to swerve out of the way, but it was too late. Salamites broadsided the armored limo.

Secret Service agents and police swarmed both cars with guns drawn. Ford was unhurt, though one of the dignitaries accompanying him, Connecticut Republican Chairman Fred Biebel, suffered a broken hand. Immediately, the limo was sent back on its way to Bradley, despite heavy damage. Salamites and his passengers, meanwhile, underwent lengthy questioning until police concluded he wasn’t at fault and released him.

Sources: "Ford Is Uninjured as His Car Is Hit in Hartford,'' New York Times, October 15, 1975; "No Accidents Since For Driver After Startling Crash," Hartford Courant, March 14, 2008.)

Q: Where is this building located? The symbol affixed to the top is a big clue.

A: The Burlingame Building of the Institute for Living, as seen from Washington Street. Finished in 1948, the eight-story building was originally used by the Institute to perform labotomies, then a new and much-heralded procedure for addressing severe mental illness.

Sources: Emporis.com and "The History of Insanity: Shameful to Treatable," New York Times, September 20, 1998.

Q: The Metropolitan District Commission, the agency that provides drinking water and wastewater treatment to Hartford and surrounding towns, began adding something to the drinking water in 1960. What was it?

A: Fluoride. The MDC initially considered letting each of its member communities vote on making the change, but the board members eventually "reasoned that since the science behind fluoridation was fairly complex, they were the only ones who could make an informed decision," according to Kevin Murphy in his 2011 book, "Water for Hartford: The Story of the Hartford Water Works and the Metropolitan District Commission."

Q: On February 24, 1961, the Federal Communications Commission granted a first-of-its-kind license to Hartford's WHCT-TV, Channel 18. What did the license allow?

A: Pay television. Coming almost a decade before HBO, this operation sent scrambled signals over the air to subscribers, who had to enter codes into special boxes conntected to their TV sets to descramble them. The pay portion of WHCT's schedule ran in the evenings from 1962 to 1969, when the partnership behind it—station owner RKO General and descrambling-box seller Zenith—concluded that 5,000 subscribers weren't enough to justify the operating costs.

WHCT, which many remember for the religous broadcasts of the Rev. Gene Scott in the 1970s and early 1980s, was located at 555 Asylum Avenue, across the street from the train station. The building is now home to ArtSpace Hartford, a mix of apartments and art spaces.

For more on WHCT, see this article by Kyle Bookholz and this New York Times obituary on Thomas F. O'Neil, the RKO General executive who led the station.

Q: Who was the first African-American elected to public office in Hartford?

A: John C. Clark Jr., who was elected to the City Council in 1955 and served until 1963. The Clark Elementary School, at 75 Clark Street, is named for him.

Q: In the 1920s, Ann Corio was living on Zion Street and attending Hartford Public High School when she embarked on a career that would earn her world acclaim as the "queen" of her profession. What was that profession?

A: Burlesque stripper. As the Hartford Courant reported in October 2010, Corio's fame was such that Harvard University made her an honorary member of the Class of 1937. The article also noted that she “quit the burlesque circuit in her prime, turned off by the increasingly crass nature of the genre.” Ann Corio died in 1999.

Q: What landmark restaurant of the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s became such a hangout for legendary Democratic State Chairman John Bailey that his family bought one of its booths and installed it in their home, hoping he’d stay in more often?

A: Scoler’s, at 260 Farmington Avenue. The ploy, incidentally, did not work. Bailey died in 1975. Scoler’s moved to Bishop’s Corner in West Hartford in 1984 and closed in 1991. (Sources: Hartford Courant, September 22, 1984, and July 26, 1996.)

Q: Who is the dashing fellow depicted in this downtown statue?

A: General Casimir Pulaski, the Polish general who died while fighting for General Washington's army in the Revolution and became known as the father of the American cavalry. The statue, built around 1970, stands adjacent to the Federal Building on Main Street, opposite the corner of Capitol Avenue. The pedestrian mall stretching behind the statue is also named after Pulaski. The Polish National Home, a center for Polish culture throughout the Hartford region, is located just around the corner, on Charter Oak Avenue.

Q: James Renwick, the architect of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, also designed a Hartford church. Which one?

A: First Presbyterian Church, built in 1870. It’s at the corner of Capitol Avenue and Clinton Street, adjacent to The Bushnell. The church's website has more on its history.

Q: For whom is the Betances School named?

A: Ramon Emeterio Betances, leader of the 1868 revolt against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico. The school was named the Kinsella School until 1985, when the Puerto Rican Political Action Committee (PRPAC) convinced the Board of Education to rename it for Betances. (Source: "Identity & Power: Puerto Rican Politics and the Challenge of Ethnicity," by Jose E. Cruz.)

Q: What Hartford radio station operated from 243 South Whitney Street from 1980 to 1988?

A: WCCC, AM and FM. The wonderful site Connecticut Radio History has some great photos from this period in the station's history. (Yeah, those are the guys from Def Leppard.) The site's full history of WCCC is here.