The Almada Lodge and Channel 3 Kids Camp

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of the magazine Connecticut Explored. You may also read it, with more photographs, at ctexplored.org. While you're there, please subscribe. The magazine is a nonprofit published by a consortium of organizations that represent the best heritage, educational, and arts organizations in the state.

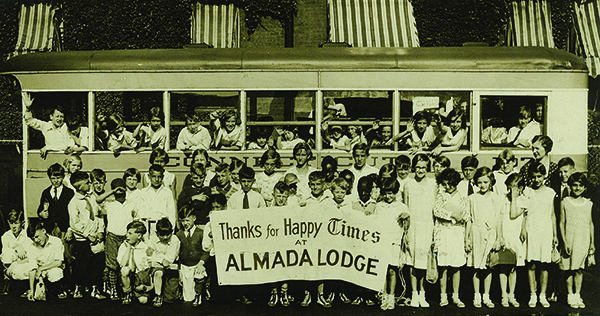

For many years, a trolley brought kids to and from the Hartford Times Farm Camp in Andover. This photo, courtesy of the Channel 3 Kids Camp, is undated but appears to have been taken in the 1920s or 1930s.

Kids have been trundling out to a spot along the Skungamaug River in Andover since 1910, arriving at first by horse or train, then by trolley, bus, and car. The name of the place has changed a few times too—from the Almada Lodge, to the Times Farm Camp, and finally to the Channel 3 Kids Camp—but one idea has remained constant: giving kids a summer camp experience regardless of their backgrounds.

The camp owes its creation to a Hartford assistance organization called the Union for Home Work. An early profile of the camp, published July 18, 1915 in the Hartford Courant, said the Union “concerns itself with poor folk who are willing to work, and it finds these in profusion throughout the East Side territory in which it is located.” The Union already operated a day nursery out of its quarters on Market Street, “giving a whole flock of babies a riotously good time in its capacious back yard which is a sort of oasis in a desert of tenements and small shops where almost everything flourishes except grass and flowers and quiet,” according to the Courant. Elizabeth S. Ayres, head of the group, wanted to provide something similar for older children but realized they “needed a little more pasturage.”

Enter Harrison B. Freeman Jr., a Hartford lawyer, state legislator, and probate judge who owned property along the Skungamaug, including a pair of farmhouses. He gave the Union full use of it, along with some money for upkeep. City kids now had a summer sanctuary in the country. The smaller farmhouse was reserved for boys, with cots set up throughout the rooms, “all looking white, neat, and inviting,” according to the Courant. Each morning, the boys swarmed across the street for breakfast in the larger house, called Almada Lodge (apparently in memory of Freeman’s first wife, Alma.) Besides a 30-seat dining room, it accommodated girls and the camp management, which included members of the Visiting Nurse Association.

Anyone standing on the wide veranda of Almada Lodge saw nothing around but woods and farmland. “There’s not another house in sight,” the Courant reported, “nor is there anything which the boys can harm in their search for amusement.” The article described kids swimming and fishing in the river but said nothing else about activities at the camp, leading one to assume campers got the same instructions as most other kids in those days: Get out of the house and don’t come back until mealtime.

Denise K. Hornbecker, the camp’s current chief executive officer, says the mission in those days wasn’t complicated: “The whole purpose was, ‘Just get kids out of the city, off the concrete.’”

In 1920, responsibility for running the camp passed from the Union to Hartford’s other daily newspaper, the Hartford Times. In 1931, the Freeman family and the Times deeded the camp to a newly formed charitable corporation, the Almada Lodge-Times Farm Camp Corporation. Throughout, the camp relied on donations to stay in operation.

But with the Times still involved, the camp never lacked for publicity. Whether it was kids lining up in Hartford neighborhoods to board buses bound for Andover or kids going through the daily flag-raising ceremony, Times reporters and photographers were on hand to ensure that readers never forgot about the camp. Well into the 1970s, the newspaper documented camp visits by dignitaries like Governor Ella Grasso, sports clinics led by the likes of University of Connecticut basketball coach Dee Rowe, and fund-raising events like a dinner featuring Hall of Fame baseball player Joe DiMaggio.

In 1976, the Times ceased publication. But the camp immediately found another media partner in WFSB-TV Channel 3, then located in downtown Hartford. The camp has been called the Channel 3 Country Camp ever since. While the station doesn’t hold any ownership in it or pay expenses, it has continued the tradition of keeping the camp in the spotlight by holding telethons and publicizing other fund-raisers.

Changing campers, changing needs

Throughout the last century, the camp held onto the most rustic aspects of country life, such as the team of donkeys that pulled cartloads of campers along Andover roads. Peter Houle, a local kid who worked at the camp in the early 1960s, used to lead the donkey team, earning himself the moniker “Donkey Boy.”

“It was super rustic,” Houle says with a laugh. “But I enjoyed it.”

Today, though, the camp is a very different place. While its footprint has shrunk—from 300 acres down to 150—it draws more kids than ever. Originally serving just 10 to 12 per summer, it now accommodates about 2,000 for one-week stays. The service area has expanded far beyond Hartford, with last year’s campers coming from more than more than 120 Connecticut communities, including Stamford and New Haven. (The camp still has a strong Hartford connection through its Holiday Light Fantasia, held each holiday season in Goodwin Park. The two-mile show, featuring more than 1 million lights set to a holiday soundtrack, is the camp’s biggest fund-raising event.) The camp requires a year-round staff of 13, in addition to the seasonal counselors, who often come from overseas.

Besides serving more kids, the camp serves more kinds of them than in generations past. Foster children, for instance, can reconnect with siblings who’ve been sent to different foster homes through the Sibling Connections program, run in partnership with the state Department of Children and Families. And for one week a year, the camp partners with the Connecticut National Guard to host children from military families, giving them a chance to relieve some of the stress of deployments and other challenges through the camaraderie of camp activities. To help prepare all kids for an increasingly complex world, there’s also an environmental education program, a teen leadership program, and even a video-production program, along with more traditional camp activities like archery, swimming, and hiking

But the camp’s biggest investment has been in reaching out to special-needs children. In 2013, the camp broke ground on Ashley’s Place, a 4,400-square-foot cabin that sleeps 64, with counseling staff and round-the-clock nursing support. Funded primarily by a $500,000 gift from the Ashway House Charitable Trust Foundation, it’s named for Ashley Leveillee, a special-needs child who passed away at age 13. Her biggest unmet wish was to go to camp. Now, the camp gives kids like Ashley a fully inclusive experience; in fact, special-needs kids make up 20 percent of campers.

Hornbecker, who’s entering her 12th summer as director, says the camp has had to change with the times, sometimes rapidly. “Families don’t look the way they did 100 years ago,” she notes. “They don’t even look the way they did when I started here.”

Ashley’s Place represents just one of the major infrastructure improvements made in recent years. Older adults who came to the camp as children may recognize the rustic Recreation Hall, built in 1940 and still used for major indoor events, but little else. The Freeman Center, built in 1995 and renovated in 2014, houses a year-round pre-school center. The camp’s health center, built in 1957, has been renovated into the Jennifer L. Hawke-Petit Health Lodge, an Americans with Disabilities Act-compliant facility that can support the first aid and medical needs of all campers. There’s also a 24-by-75-foot swimming pool and a new playground. They all compliment 15 sleeping cabins and Turn Lodge, built in 1983 to serve as the dining hall and central building of the complex.

Hornbecker estimates that $3.5 million has been spent on renovations in recent years, including much-needed improvements to the septic and water systems. “We’ve transformed this into a place where kids from all backgrounds can come for a respite,” she says.

Of course, it’s also a respite for parents. Faced with having to hold multiple jobs, raise kids without second parents, and other 21st-century challenges, parents need the relief of summer camp more than ever, according to Hornbecker. Some things never change.